Acute hepatitis B virus infection:

Thirty percent of patients with acute hepatitis B develop icteric hepatitis, while roughly seventy percent have subclinical or anicteric hepatitis. Patients with underlying liver disease or other hepatitis viruses may have a more severe case of the disease.

One to six months pass during the incubation phase. During the prodromal stage, a syndrome resembling serum sickness may appear, followed by constitutional symptoms, anorexia, nausea, jaundice, and discomfort in the right upper quadrant. In most cases, the symptoms and jaundice go away after one to three months. A rare condition, cute liver failure affects 0.1 to 0.5 percent of patients.

Acute hepatitis with HBsAg positivity can also be diagnosed as:

(1) Acute hepatitis B

(2) Chronic hepatitis B exacerbations, such as acute hepatitis brought on by drugs and other toxins in a chronic hepatitis B infected person, reactivation of chronic hepatitis B, or superinfection of a chronic hepatitis B infection with hepatitis C, A, E, or D virus.

Alanine and aspartate aminotransferase levels (ALT and AST) are elevated during the acute phase of acute hepatitis B; values up to 1,000 to 2,000 IU/L are typically seen during this phase, with ALT being higher than AST. The serum levels of lactic dehydrogenase and alkaline phosphatase are typically only slightly elevated (less than threefold). Both the direct and indirect fractions of the bilirubin are variablely elevated. Patients with an-icteric hepatitis may have normal serum bilirubin levels. Except in cases of chronic, severe disease, serum albumin rarely decreases. The best prognosis predictor is the prothrombin time.

Normalisation of serum aminotransferases takes one to four months to happen in patients who make a full recovery. Persistent elevation of serum ALT for more than six months may indicate progression to chronic hepatitis.

Chronic hepatitis B virus infection:

The age of infection has a major impact on how quickly acute hepatitis B turns into chronic hepatitis B. The rate is roughly 90% for infections acquired during pregnancy, 20% to 50% for infections acquired between ages one and five, and less than 5% for infections acquired as adults. Hepatitis B virus infection is referred to as chronic if HBsAg is persistently positive for more than six months.

A thorough history and physical examination with a focus on determining the severity of underlying liver disease and determining treatment eligibility should be performed on people with chronic hepatitis B. Alcohol use, family history of HBV infection, liver disease, and liver cancer, history of complications that would suggest underlying cirrhosis (such as ascites, hematemesis, and mental status changes), and other factors, such as underlying cardiopulmonary disease, past or present psychiatric issues, autoimmune diseases, and other co-morbid conditions, should all be highlighted in the history. Evaluation of advanced liver disease stigmata, such as spider angiomata, palmar erythema, splenomegaly, jaundice, or caput medusa, should be part of a physical examination. Clinicians should be aware, though, that the absence of any one of these findings does not rule out the possibility of underlying cirrhosis.

Patients diagnosed with Chronic Hepatitis B should also be mandatorily screened for HIV and Hepatitis C due to common modes of transmission.

Laboratory Diagnosis :

Blood is the preferred specimen, and 3-5 ml of venous blood needs to be drawn and placed in a sterile, dry, and labelled vial. Avoid hemolyzed samples because they might make it difficult for tests to detect markers accurately.

• Within 4 hours of collection, serum from clotted blood should be removed and stored at -20°C to -70°C to prevent the degradation of viral nucleic acid in the specimen.

• Serum samples can be stored for a maximum of 7 days at 4-8°C and long term storage beyond 7 days should be done at -80 °C.

Serological markers for Chronic Hepatitis B infection:

1) Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg):

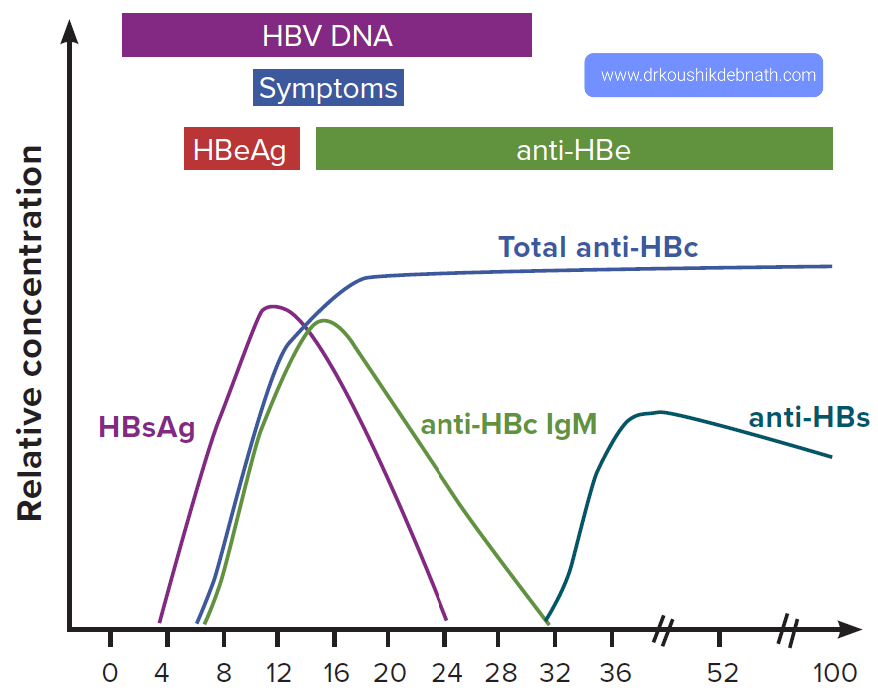

After infection, HBV DNA is the first serological marker, followed by HBsAg. Even before the elevation of liver enzymes and the start of a clinical illness, the antigen is detectable. Typically, it goes away 2 months after the start of the clinical illness, but in some cases, such as with chronic infections, it can persist for up to 6 months. Therefore, if this test results in a positive result, the patient is likely contagious, and if it results in a negative result, chronic infection is usually ruled out.

2) Anti-HBsAg (Antibody to HBV surface antigen):

This antibody manifests when HBsAg is no longer detectable (antibody to HBV surface antigen).It is a protective antibody that shows immunity to HBV from either a prior infection or vaccination.Anti-HBs antibodies have a protective level of 10 mIU/ml.

3) Anti-HBc ( Antibody to HBV core antigen):

The earliest antibody marker after infection is the anti-HBcIgM (antibody to HBV core antigen). The anti-HBcIgM is the first antibody marker to be detected in blood, appearing in serum a week or two after HBsAg does. Since the anti-HBcIgG antibody may last a lifetime, it serves as a useful marker for previous HBV infection. Total antibody to HBc indicates past or ongoing infection because IgM anti-HBc is only present in acute infections and is replaced by IgG after six months. IgG anti-HBc is a trustworthy indicator of prior HBV infection because it endures even after anti-HBs titers drop to undetectable levels many years following recovery from HBV infection.

4) HBeAg:

In acute, resolving cases, it typically vanishes within a few weeks after appearing in the blood concurrently with or shortly after HBsAg.The presence of this antigen is also used as a criterion for selecting patients for treatment because it is an indicator of active intrahepatic viral replication and, as a result, indicates that the person is highly contagious.Anti-HBe then appears after its disappearance. In the majority of acute hepatitis B cases, testing for HBeAg is not required for routine diagnostic purposes. Instead, individuals in whom HBeAg is a significant marker of viral replication and correlates qualitatively with more quantitative markers of active replication, such as serum HBV DNA detected using molecular techniques, should have their HBeAg levels tested.

5)Anti-HBeAg :

It has prognostic implications as the appearance of anti-HBe in acute hepatitis B implies a high likelihood that HBV infection will resolve spontaneously. Anti-HBe's presence in blood denotes low infectivity.

Serologic markers-caveats:

- Precore mutants have mutations in the precore region, which abolishes HBeAg production, or in the core promoter region, which downregulates HBeAg production. Despite possibly producing anti-HBe and anti-HBc antibodies, these patients do not produce HBeAg.

- The second group of so-called escape mutants (due to mutations in a determinant of S gene preventing them from being neutralised by the anti-HBs) is seen in some infants born to HBeAg positive mothers and in liver transplant patients who have received combined immunisation with anti-HBV immunoglobulin and vaccine. This has no effect on viral replication; in fact, such cases are more difficult to treat and have a higher risk of turning into cirrhosis.

- HBeAg and HBsAg may both be suppressed by co-infection with HCV.

- HBcAb is occasionally the only serological marker that can be found. This could be either because of Co-infection with HCV or HIV, Remote infection, "Window" period between HBsAg and HBsAb, False positive test result - HBcAb is marker most prone to false positives or Resolved HBV with diminishing anti-HBs levels.

Hepatitis B Occult infection (OBI)

Viral DNA in blood that is in motion without HBsAg being visible. HBV DNA and anti-HBc would be the only remaining markers after anti-HBe disappears.

Molecular Diagnostics :

HBV DNA (Quantitative):

Hepatitis B DNA PCR is a molecular test that can detect the presence of HBV DNA, which is a marker of viral replication and infectivity like HBeAg.Therefore, HBV DNA is used in clinical practise to track therapy and evaluate patient response to it, such as every three months for years when the patient is taking oral agents and every month for six to twelve months if the patient is taking PEG/IFN. The identification of occult HBV infection is another use for it.

Genotyping and Resistance Testing :

The genotyping is recommended for both epidemiological purposes in the case of an outbreak investigation and for the detection of mutations that confer resistance to antiviral agents. Eight different HBV genotypes (A to H) have been identified through genotyping of patient isolates. Sequencing and hybridization techniques (Line Probe Assay) are used for genotyping.

Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B:

Candidates for treatment -

- Regardless of ALT levels, HBeAg status, or HBV DNA levels, treatment for all adults, adolescents, and kids with CHB and signs of compensated or decompensated cirrhosis should be prioritised.

- Regardless of HBeAg status, treatment is advised for adults with CHB who do not have cirrhosis but are older than 30 (in particular), have persistently abnormal ALT levels, and show evidence of high-level HBV replication (HBV DNA >20 000 IU/mL).

Whom NOT to Treat :

- In people without signs of cirrhosis, with persistently normal ALT levels, and with low levels of HBV replication (HBV DNA 2000 IU/mL), regardless of HBeAg status or age, antiviral therapy is not advised and can be postponed.

- In the absence of HBV DNA testing, treatment can be postponed in HBeAg-positive people 30 years of age or younger with persistently normal ALT levels.

- All CHB patients need to be monitored regularly, but it's especially important for those who don't currently fit the guidelines for whether or not to receive treatment, to find out if antiviral therapy will ever be necessary to stop the progression of liver disease. These people include those under 30 years old without cirrhosis who have HBV DNA levels greater than 20,000 IU/mL but persistently normal ALT.

Treatment modalities of Chronic Hepatitis B Infection :

- The NAs with a high barrier to drug resistance (tenofovir or entecavir) are advised for all adults, adolescents, and children aged 12 years or older for whom antiviral therapy is indicated.

- Tenofovir may be preferred as the medication of choice in women of childbearing age in the event of pregnancy. Pregnancy is not advised when using entecavir.

- Patients with a risk of developing Entecavir resistance who have taken lamivudine are advised to use tenofovir instead.

- Children between the ages of 2 and 11 should not take entecavir.

- Entecavir may be preferred over Tenofovir in Age > 60, history of fragility fractures or osteoporosis; use of other drugs that worsen bone density, altered renal function (eGFR 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, albuminuria > 30 mg/24 hr, moderate dipstick proteinuria, Low phosphate (2.5 mg/dL) or in patients receiving hemodialysis.

- Drugs with a low barrier to resistance (lamivudine, adefovir, or telbivudine) are available but not advised as they promote drug resistance. Tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (TAF) is the drug of choice in patients with reduced renal function or bone disease bone toxicities, where entecavir is contraindicated.

Prior to, during, and after treatment, CHB patients are monitored for disease progression and treatment response.It is advised that the following be checked at least once a year:

- HBV DNA levels (where HBV DNA testing is available), HBsAg, HBeAg, and ALT levels (and AST for APRI)

- Non-invasive tests (APRI score, FIB-4, or FibroScan) to determine whether fibrosis has gotten worse or whether cirrhosis has developed in people who didn't have it at the start.

- If receiving treatment, adherence needs to be checked frequently and at each appointment.

Given the risk of reactivation, which can also result in severe acute-on-chronic liver injury, all individuals with cirrhosis based on clinical evidence (or adults with an APRI score >2) require lifelong treatment with NAs.

Hepatitis B treatment should not typically be stopped without consulting medical professionals with the necessary knowledge, who should be found in specialised facilities.

When deciding to stop therapy, it is important to carefully weigh the financial impact of continuing to pay for medication and monitoring versus the risk of virological relapse, decompensation, and death. Antiviral treatment should not be stopped for any cirrhotic patients due to the possibility of reactivation, which could result in decompensation and death.

No comments:

Post a Comment